The bush pilot delivered Felix Wölk and Thomas Bing to a completely uninhabited Alaskan wilderness. They wanted to paddle down Beaver Creek for three weeks and be the first to fly the White Mountains. The folding boat was full to the gunwales with supplies, camping gear and Hike & Fly equipment: and something no one should be without - anti-bear pepper spray.

It is midnight, and the sun glows on the horizon. On a branch of Beaver Creek we push on along our magical but distinctly winding odyssey, towards the Yukon Flats. The pink night sky is reflected in the calm, oily flat water. A paradise of stillness. We do not speak. Tommy and I have been eighteen days in this humanless wilderness. My mind reflects: on the brown bear who destroyed my tent, on the storm that blew away our camp, and on the fantastical paraglider flight in the light of the midnight sun.

Into the wild

Our adventure just south of the Arctic Circle began on June 24th. Our folding boat is good for a 360kg payload. Provisions, survival equipment, paragliders, camera equipment. Our goal is to make the first flight on the White Mountains of the Tanana Hills, as well as at the Victoria Massif – mountains which can only be reached in summer by the course of the ‚Beaver‘, which winds its way through sub-polar Alaska for 300 kilometres. For three weeks we will have no contact with the outside world, nor rescue facilities – because we have dispensed with satellite phone. We are to exist exclusively with and within nature: by water, air and muscle power.

It is spring in Alaska. Beaver Creek presents a scene of desolation. Tommy is an experienced canoeist and our helmsman, searching out the correct line. He understands the ‘visual funnel’ system – a tapering of smooth water indicating its depth. My position is paddling powerhouse, and bow lookout. In no time at all we are a coordinated team. In the rapids, communication becomes brief and full of meaning. “Roots at eleven o’clock: twenty metres!” “Got it.” “Funnel right. Then tree trunk right!” “Paddle!!” We are on the river nine hours a day. After five days we reach the foothills of the White Mountains. In the northern light the rock of these mountains seems pale and somehow lifeless. We make our camp on a river sandbank, the base for our first flying attempt. We wait in the no-wind weather. For hours, days, we study the cloud formations of this arctic sky. Humidity after a rain shower turns our camp into an immediate nest of mosquitos. Only the fire, burning day and night, gives us relief.

Night turns to Day

After a stormy day we tackle the ridge at around 9 pm, first climbing towards the mountains through steep overgrown forest following animal tracks. Dead trees snap like matchwood. Broken wood, bear manure and elk droppings indicate that wild animals are about. At the top of the ridge the wind is gusty, accompanying the retreating overdevelopment. We wait patiently. From the space between the horizon and a black wall of cloud the midnight sun throws its orange light on the white rocks. It is one o’clock in the morning. A light pull on the A-lines has the canopy rising up from between scrappy miniature fir trees. I let the wing fly, call “Go” to Tommy and take three large paces. We lift off. Airborne in Alaska! Where exactly we don’t know: this mountain does not have a name. We glide over the deserted wilderness. The valley is in shadow. Below us the course of the Beaver glimmers silver in a black forest. The only sign of civilisation is a green spot on the bank – the plastic groundsheet of our ‘shelter’. In the midst of this vastness the tiny home looks a pitiful attempt at human domination.

The Wilderness Strikes Back

At the foot of Victoria Mountain things get serious. A full-grown brown bear is rummaging around our camp. It’s as Tommy said: “When you least expect one, there they are.” We draw our pepper sprays and try to drive him off. As he turns away his nose draws him to our tents, 150 metres away. Goose feathers. He rips open my tent and tears apart my sleeping bag and camping mat into smithereens. I don’t feel too good – it is by pure chance that I’m not lying inside. A nip in the leg, the taste of blood; I might have become dinner. A bear might come back to this bonanza of a find, so we quickly set about a change of refuge. The nights become harder from now on with only one sleeping bag.

No chance on Victoria Mountain

The Victoria massif turned out to be stormy. Rotor clouds formed in streets, ice clouds streamed overhead like threads. The wind lashed Beaver Creek, leaving streaks on the water. Two attempts to fly the mountains failed. After three weeks we reached our pick-up point. It is a strange feeling when the bush pilot thunders over our heads in his old propeller-driven contraption. In this isolation, human activity had become foreign. When we had breakfast in ‘Sven‘s Guesthouse’, Fairbanks, the background of civilisation sounded like noisy chaos. I yearned for the wind in the woods, the murmur of the river, and the kaleidoscope of animal voices.

The Equipment

The Team

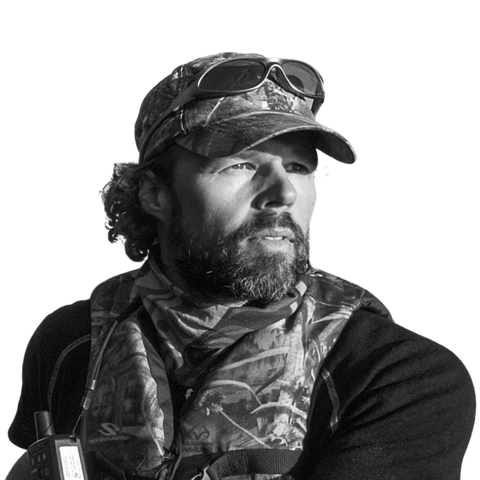

Felix Wölk

Felix is a paraglider and hangglider pilot, parachutist and mountain sportsman of the old school. For two decades he has enjoyed a worldwide reputation as a celebrated paragliding photographer.

Thomas Bing

Thomas is a passionate canoeist, paraglider pilot and globetrotter. Faithful to his motto “When the going gets tough, the tough get going”, he has acquired a wealth of survival experience in inhospitable regions.